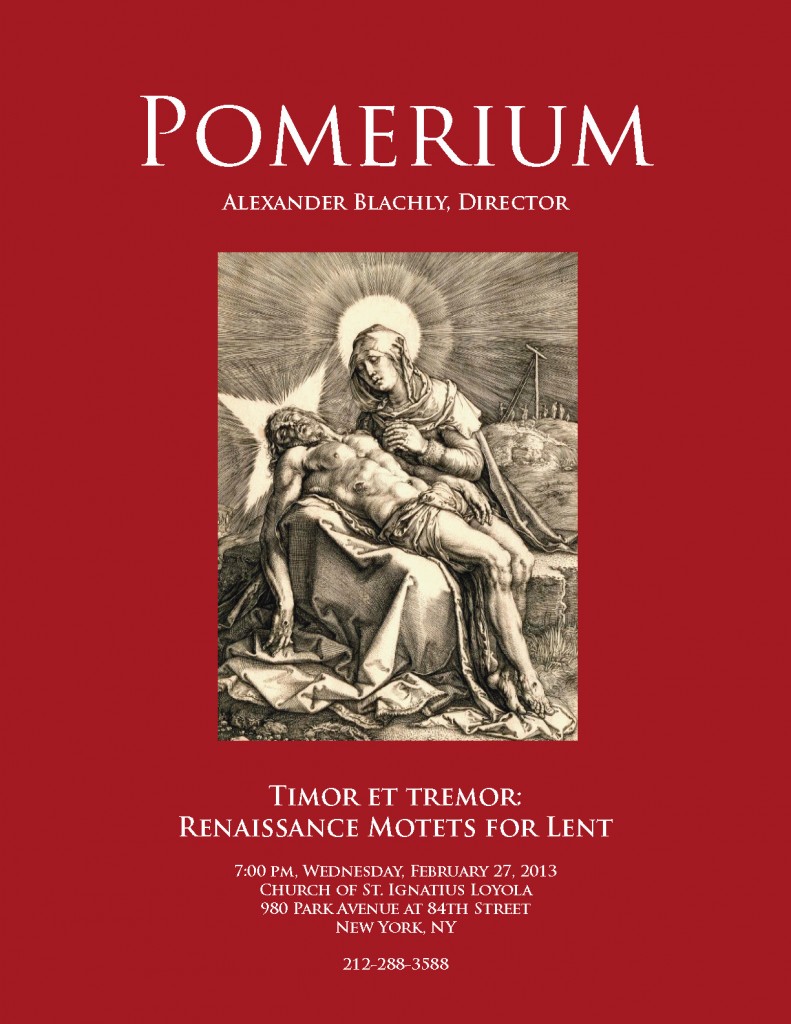

Sacred Music in a Sacred Space Presents

Sacred Music in a Sacred Space Presents

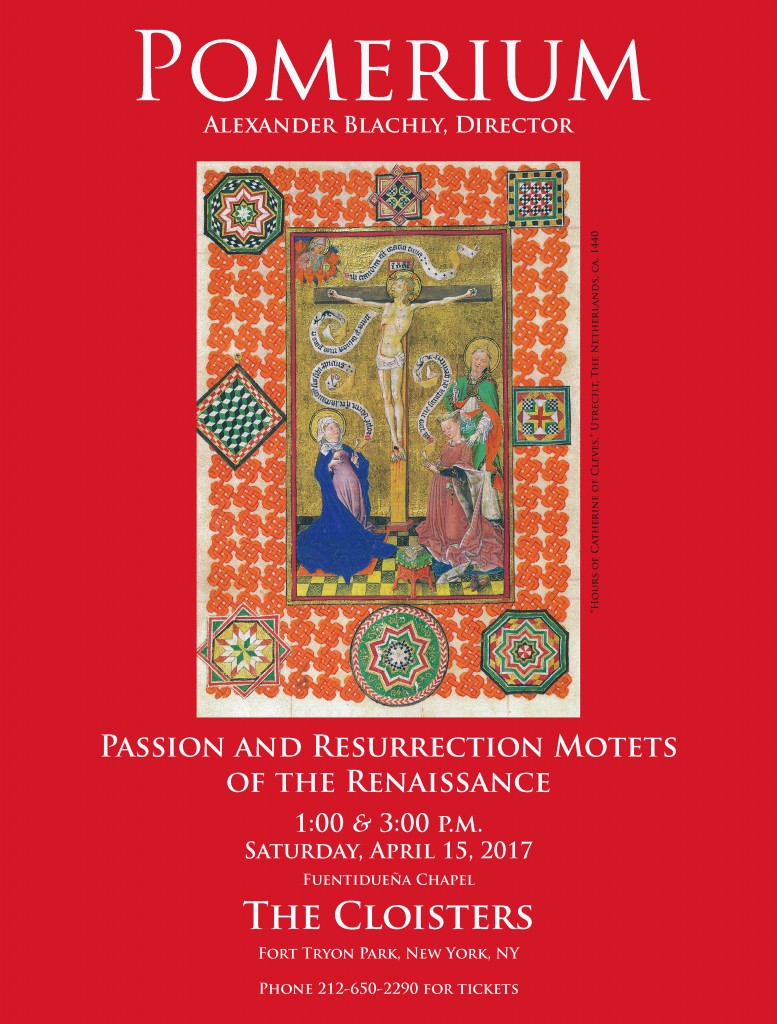

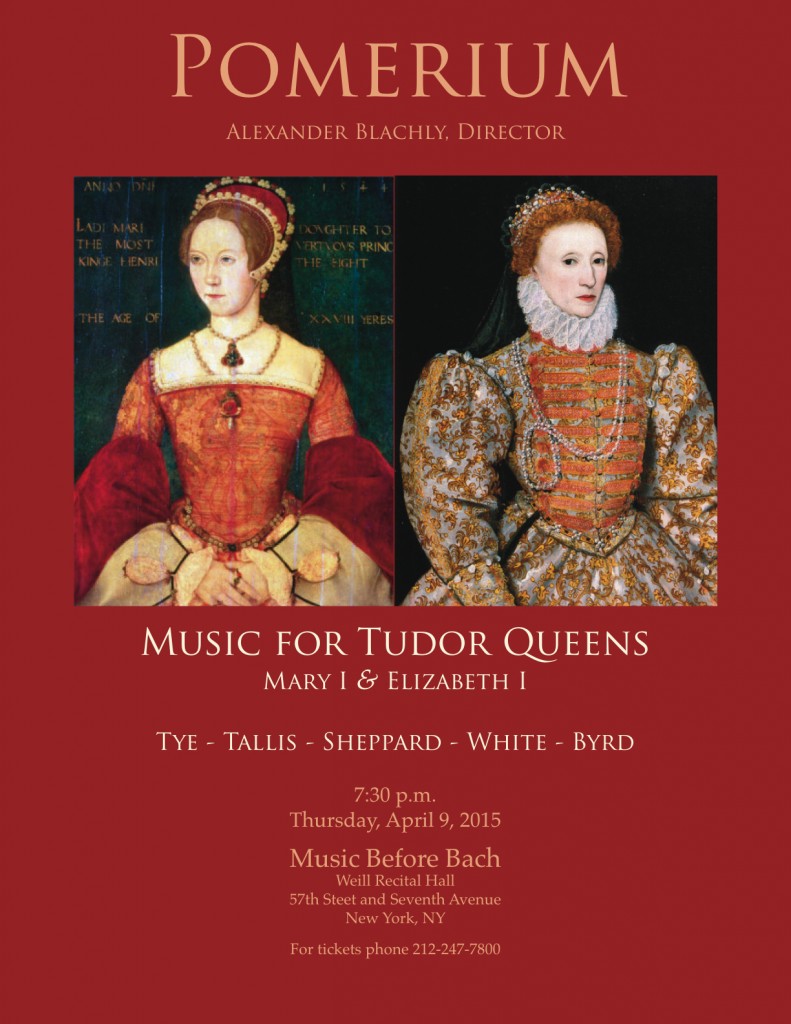

POMERIUM

Alexander Blachly, Director

Timor et tremor:

Renaissance Motets for Lent

7:00 p.m., Wednesday, February 27, 2013

St. Ignatius Loyola Church, New York, NY

Audi, benigne conditor (Hymn for Lent I) Guillaume Du Fay (ca. 1397-1474)

Invocabit me (Lent I Introit) York Graduale (Oxford, 15th cent.)

Super flumina Babylonis (Motet) G. P. da Palestrina (1525-1594)

Angelis suis (Lent I Gradual) York Graduale

In ieiunio et fletu (Responsory) Thomas Tallis (1505-1585)

Derelinquit impius (Responsory) Thomas Tallis

Stabat mater (Lenten Sequence) Josquin Desprez (ca. 1450-1521)

INTERMISSION

Audi, benigne conditor (Motet for Lent) Orlande de Lassus (1532-1594)

Emendemus in melius (Responsory for Lent I) William Byrd (1540-1643)

Christe qui lux es et dies (Hymn) William Byrd

Lamentationes Ieremiae Robert White (1538-1574)

O vos omnes Alfonso Ferrabosco (1543-1588)

Timor et tremor, à6 Orlande de Lassus

POMERIUM

Elizabeth Baber, Kristina Boerger, Melissa Fogarty,

Michele Kennedy, Dominique Surh – sopranos

Luthien Brackett – mezzo-soprano

Robert Isaacs – countertenor

Thom Baker, Neil Farrell, Michael Steinberger – tenors

Jeffrey Johnson, Thomas McCargar – baritones

Kurt-Owen Richards – bass

COMMENTARY ON THE PROGRAM

by Alexander Blachly

Lent was originally a time of preparation for the catechumens (those aspiring to be Christians) preceding their confirmation on Easter Sunday. Like Advent, the period before Easter serves as a penitential season of introspection, confession, and reconciliation, when festive music gives way to more somber sounds. The austerity of Lenten penitence finds musical expression in this evening’s program in Du Fay’s early Renaissance setting of the great Lenten hymn Audi, benigne conditor. The words, once attributed to Pope Gregory the Great (reigned 590-604), pray that those fasting over forty days might enjoy the rewards of outward abstinence: the Maker’s forgiveness of sin within. Du Fay’s music alternates odd verses sung to the traditional Gregorian chant melody with even verses sung in a three-part harmonization of the chant melody transformed by paraphrase (heard in the top voice). Like most Latin hymns, Audi, benigne conditor ends with a doxology stanza praising the Trinity.

The ancient Gregorian chant introit for the First Sunday of Lent is cast in the melodically dark Tone 8. The source of the version heard here is a fifteenth-century book of Mass chants now in the Bodleian Library in Oxford (Mus. Ms. Lat. Liturg. b. 5), a book that transmits the rite of York, which, while nearly identical for most pieces with the Roman rite, exhibits occasional local variants. Also from Lat. Liturg. b. 5 comes the fourth item in our program, the gradual Angelis suis from the same Mass. Angelis suis shares with the Easter gradual Haec dies and a number of other graduals some notable melodic turns of phrase that are among the highlights of the Gregorian repertoire.

Though no Alleluia or Gloria in excelsis sounds in church during Lent, the season’s music expresses in its memorable melodies and harmonies the intensity of the penitential season. Indeed, with the exception of the opening Du Fay hymn, the polyphonic works on our program reveal that the “somber” music of Lent in the later Renaissance was in fact often highly charged harmonically. The theme of exile expressed in the memorable words of Super flumina Babylonis from Psalm 136 (Ps. 137 in the Protestant psalter) is understood in Lent to refer to the Fall of Man and man’s subsequent exile from God. Even Palestrina, who normally shunned coloristic effects in favor of a transcendent calm, sets Super flumina with some melodies outlining diminished intervals and with harmonies that incorporate an occasional telling dissonance to express the Psalm’s themes of loss and deprivation.

Included in the collection Tallis and Byrd published jointly in 1575 with a monopoly from Queen Elizabeth are the two motets by that follow—settings of responsory texts from the Matins service of Lent I. Thought to be among Tallis’s last compositions, In ieiunio et fletu (text from Joel 2) and Derelinquit impius (text from Isaiah) both show the acknowledged master experimenting with new means of expression at the end of his career. In ieiunio et fletu opens with each of the five voices in turn singing the motif associated with the words “In ieiunio et fletu,” but with each voice entering on a different note of the scale—and with the final voice entering on a note that is not even in the scale defined by the first four voices. Tallis’s highly chromatic and unsettled music seems to have no tonal anchor, as though to express the anxiety of Joel’s “priests,” who argue desperately for God to have mercy on his people, who are his inheritance. Derelinquit impius, similarly, opens with five statements of the motif associated with “Derelinquit impius viam suam,” each starting on a different note of the scale. Passing harmonies that include F-sharp one moment, F-natural a moment later, C-sharp immediatey followed by C-natural, G-sharp vying with G-natural, prevent the music from settling into a single harmonic home; the climax comes at the end when a series of overlapping descending scales continue, and increase, the “multi-tonal” effect established earlier, which is not so different from the simultaneous sounding of different keys in some of Stravinsky’s music of nearly four centuries later.

Josquin’s five-voice Stabat mater was judged during his lifetime to be one of his greatest works. It features prominently in the magnificent musical anthology known as the Chigi manuscript (Vatican City, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, MS Chigi C VIII 234, copied by the Alamire workshop ca. 1501); it is also found in an anthology copied in the same scriptorium ca. 1515 (Brussels, Bibliotèque royale, MS 215-216) of music for the newly authorized feast of the Seven Sorrows—a feast that until 1903 was celebrated on the Saturday before Passion Sunday. Liturgically, the Stabat mater text still figures prominently in both Lenten and Seven Sorrows (now September 15) devotions. To serve as an anchor voice, or cantus firmus, for his setting, Josquin chose the tenor of a French chanson by Gilles Binchois (ca. 1400-1460), Comme femme desconfortée, sounding in slow motion. By situating Binchois’s greatly augmented voice, singing its French words, in the middle of four other voices singing the Stabat mater poem, often in declamatory fashion, Josquin sacralized the French words, which are now to be understood as the words not of a bereaved lover but of the anguished Virgin Mary: “Like a woman in agony, distraut above all others, I am one who has no further hope in life and cannot be consoled.” The particular genius of Josquin’s setting is that he makes each change of pitch in the slow-moving cantus firmus appear inevitable, even as he achieves unusually moving harmonic effects to evoke the Virgin’s grief.

INTERMISSION

Lassus sets the same Lenten hymn as Du Fay, Audi, benigne conditor, but now as a motet in two large sections comprising two stanzas each (omitting the doxology Stanza 5). First appearing in print in 1568, Audi, benigne conditor figures among Lassus’s relatively early works (the earliest date from 1555, the latest from 1594). For a composer famous for his musical rhetoric, that is, capturing in music the meaning and mood of the words being set, this motet seems an oddly cheerful plea to God to grant forgiveness to a faithful servant fasting in penitence. Since Lassus did not set words carelessly, we may interpret the bright sound of this work to represent the composer’s Christian faith in heavenly rewards.

From the jointly edited anthology in which Tallis included his In ieiunio et fletu and Derelinquit impius, Byrd positioned Emendemus in melius as his first motet, which scholar Joseph Kerman takes to be an indication that Byrd thought especially highly of this work. Set almost entirely in homorhythm (chordally), with five voices declaiming the Lenten responsory text simultaneously, Byrd achieves a moving, emotional result by virtue of his exquisite harmonies. Only at the very end do the individual voices speak independently, as they sing the words Libera me (“liberate me”).

Byrd’s unusual setting of the Lenten hymn Christe qui lux es et dies, which survives only in the so-called Dow Partbooks of 1581-88, takes Robert White’s setting of the same hymn as a model. Both composers present the traditional chant melody in an unbroken chain of breves, with all other voices set to the same rhythm, in effect “harmonizing” a chant that is still sung in chant rhythm. Unlike White, Byrd puts the chant melody in the Bassus in the first polyphonic verse, in the Tenor in the next verse, in Contratenor in the verse following, then in Medius, and finally in the top voice, the Superius. As unusual as the procedure are Byrd’s continually surprising harmonies, which one might almost mistake for those of a composer living centuries later.

Robert White was recognized as one of the leading composers in the Chapel Royal during the early years of Elizabeth I’s reign (1558-1603). Though a Catholic, he, like Byrd and Tallis, wrote Anglican sacred music to English words but was also allowed to write motets and Lamentations in Latin. Scholar David Mateer has referred to White’s two settings of Lamentations as “particularly fine,” adding that they “represent a high point of Elizabethan choral music.” The Lamentations heard here, for five voices, survive uniquely in the retrospective anthology copied by Robert Dow in the 1580s, well after White’s death. In the Contratenor and Tenor partbooks Dow inscribed the following tribute, somewhat garbled in syntax but clear enough in meaning: “Non ita moesta sonant plangentis verba Prophetae, Quam sonat authoris musica moesta mei,” which translates as “Not so sad do the words of the weeping prophet sound [referring to Jeremiah’s Lamentations] As does the music of my author.”

White’s prevailing approach to composition, also adopted by Tallis and Byrd, was to introduce the voices of the choir one after the other in imitation, building up the texture from a single voice to five voices, occasionally with one or more voices briefly echoing one or two others, then to juxtapose these passages of contrapuntal independence with passages in which all the voices sing together in the same rhythm. Josquin Desprez had already mastered this approach at the beginning of the sixteenth century, but the English composers of the second half of the century practiced it with an identifiably national harmonic sensibility, making a virtue of alternating B-flat and B-natural, E-flat and E-natural, F-sharp and F-natural, and C-sharp and C-natural in rapid succession (heard earlier in this program to fine effect in the two motets by Tallis). When the technique involves more than one voice, musicians call the interaction a “false relation.” When it is in a single voice it is regarded as linear chromaticism. The English sound is notable for its harmonic richness, evident also in White’s Lamentations at the changes of tonal center whenever the text moves from one statement to another.

Alfonso Ferrabosco, an Italian by birth, served Queen Elizabeth I as a courtier on and off for sixteen years, beginning in 1562. When he wasn’t in England he is known to have worked for the French royal court and the duke of Savoy and to have spent time in Rome and Bologna. He was highly valued everywhere for his musical skills, but his efforts to navigate between Protestant England (where he was suspected of harboring Catholic sentiments) and the Inquisition in Italy (where he was suspected of being a spy for the English crown) led to a troubled career. The text of O vos omnes, taken from one of the verses in the Lamentations of Jeremiah set by White, is sung as the fifth responsory of Holy Saturday Matins, on which occasion the Old Testament words are understood to be Jesus’ as well.

Orlande de Lassus was the most famous composer in Europe during most of his career and by far the most productive. Only occasionally did he write highly chromatic music, his Timor et tremor of 1564 being one of those occasions—and a notable one at that. The text is a collection of verses from Psalms 55, 57, 61, 71, and 31. When Alfonso Ferrabosco’s setting of the same verses was published in the Sacrae cantiones…de festis praecipuis totius anni (“Sacred Songs…for the Major Feasts of the Whole Year”) by Catharine Gerlach in Nuremberg in 1585, it was one of several motets listed under the heading “Dominica Palmarum et de Passione Domini” (appropriate for Palm Sunday and Passiontide). It may be fair to assume, therefore, that when Lassus’s setting was published in the same city 21 years earlier, it likewise was intended to be sung at the end of Lent.

Though Lassus’s music generally may be said to stand at some remove from the peaceful calm of Palestrina and the other composers of the Roman school, in Timor et tremor the contrast reaches new heights. Lassus was drawn to the Psalms as a source of inspiration all his life, yet the extremity of the emotions in the verses chosen here inspired a work that can only be called Mannerist, in that it enlists exaggeration of Lassus’s usual procedures for greater emotional impact. Throughout this extraordinary motet the voices sing loud, then soft, then loud again as the music veers from one tonal center to another, evoking in turn the sentiments of “fear and trembling,” “dread,” “mercy,” “trust,” and “damnation” (“let me not be confounded”). The climax comes at the end, when the sopranos sing a series of rapid-fire sycopations in their highest range to the words “non confundar,” while the lower voices provide an anchor against the storm-tossed waves above them. This is about as far a cry from Palestrina’s unhurried style as Renaissance sacred music could get in the year 1564. Only with the polyphonic works of such later Mannerists as Giaches de Wert and Carlo Gesualdo would sacred music again reach comparable heights of extroversion.

Tonight’s program shows that the stylistic range in sacred music extending from the early Renaissance (Du Fay’s Audi benigne conditor) to the late Renaissance (Lassus’s Timor et tremor) is considerable. What all the works in question have in common is a commitment to counterpoint, especially imitative counterpoint, where the voice-parts function as truly independent melodies following strict rules for the preparation and resolution of dissonance. The result is complex music that avoids superficiality, that shows endlessly inventive effects achieved within its restrictions, and that because of its prevailingly serious mood seems especially well suited to intensifying liturgical devotion. It is understandable, therefore, why the Renaissance, especially the sixteenth century, has long been known as the Golden Age of Polyphony, referring particularly to the music composed for liturgical enrichment.

TEXTS & TRANSLATIONS

Audi benigne Conditor Guillaume Du Fay

Audi benigne Conditor O kindly Maker, hear, we pray,

nostras preces cum flectibus our tearful prayers in holy fast,

in hoc sacro ieiunio, a time of inward penitence

fusas quadragenario. spread out full forty days to last.

Scrutator alme cordium, O kindly searcher of our hearts,

infirma tu scis virium; you know the weakness of our power:

ad te reversis exibe now show us as we turn to you

remissionis graciam. remission’s saving grace this hour.

Multum quidem peccavimus, Yes, truly we have greatly sinned,

sed parce confitentibus, yet mercy on us trusting show,

ad laudem tui nominis and for the praise of your great name

confer medelam languidis. restore health to us, sick, below.

Sic corpus extra conteri Thus grant our body outwardly

dona per astinenciam: to suffer much from abstinence,

ieiuverunt mens sobria that we with sober mind abstain

a labe prorsus criminum. from sins with all due penitence.

Presta, beata Trinitas, O blessed Trinity, do guarantee,

concede, simplex Unitas, agreeing, simple Unity,

ut fructuosa sint tuis that to your servants fasting here

ieiuniorum munera. Amen. the fruitful prize might given be. Amen.

Invocabit me Chant introit

Invocabit me, et ego exaudiam eum, He will cry to me, and I will hear him:

eripiam eum, et glorificabo eum: I will deliver him, and I will glorify him:

longitudine dierum adimplebo eum. I will fill him him with length of days.

—Psalm 90: 15, 16

Ps. Qui habitat in adjutorio Altissimi, Ps. He that dwells in the aid of the Most High

in proteccione Dei celi commorabitur. will abide under the protection of the God of Heaven.

—Psalm 90: 1

Super flumina Babilonis Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina

Super flumina Babilionis, illic sedimus By the waters of Babylon, there we sat

et flevimus, dum recordaremur tui, down and wept when we remembered thee,

Sion: in salicibus in medio ejus O Sion; on the willow trees therein

suspendimus organa nostra. we hanged up our harps.

Angelis suis Chant gradual

Angelis suis mandavit de te, He has commended you to his angels,

ut custodiant te in omnibus viis that they should watch over you in all your

tuis. ways.

V. In manibus portabunt te, ne V. In their hands they will bear you up,

unquam offendas ad lapidem lest you ever dash your foot against a

pedem tuum. stone.

—Ps. 90: 11-12

In ieiunio et fletu Thomas Tallis

In ieiunio et fletu orabant sacerdotes, With fasting and weeping the priests prayed,

Parce, Domine, populo tuo et ne des Spare, O Lord, your people, and give not

haereditatem tuam in perditionem; your heritance to destruction;

inter vestibulum et altare plorabant Between the porch and the altar the priests

sacerdotes, dicentes, Parce, Domine, wept, saying, Spare, O Lord, spare your

parce populo tuo. people.

—Joel 2: 12a, 17b

Derelinquit impius Thomas Tallis

Derelinquit impius viam suam, May the wicked one forsake his way,

et vir iniquus cogitationes suas, and the evil man his thoughts.

et revertatur ad Dominum, et Let him turn to the Lord, and

miserebitur eius, quia benignus he will have mercy on him, for he is

et misericors est, Dominus Deus. kind and merciful, the Lord our God.

—Isaiah 55: 7

Stabat mater Josquin Desprez

Stabat mater dolorosa The sorrowing Mother stood

Juxta crucem lacrimosa weeping near the cross

Dum pendebat Filius. on which her Son hung.

Cujus animam gementem, Her weeping soul,

Contristatam et dolentem, sorrowful and grieving,

Pertransivit gladius. a sword had pierced.

O quam tristis et afflicta O how sad and afflicted

Fuit illa benedicta was that blessed one,

Mater Unigeniti. the Mother of the Only-begotten.

Que merebat et dolebat, She grieved and mourned

Et tremebat dum videbat and trembled when she saw

Nati penas inclyti. the sufferings of her glorious Son.

Quis est homo qui non fleret Who is the man who would not weep

Christi matrem si videret to see the Mother of Christ

In tanto supplicio? in such agony?

Quis non posset contristari Who would not be saddened

Piam matrem contemplari to contemplate the holy Mother

Dolentem cum Filio? grieving for her Son?

Pro peccatis sue gentis For the sins of His people

Jesum vidit in tormentis she sees Jesus in torment,

Et flagellis subditum. subjected to a scourging.

Vidit suum dulcem natum She sees her sweet Son

Morientem desolatum dying desolate

Dum emisit spiritum. as He gives up the spirit.

Eya mater, fons amoris, Oh, Mother, fount of love, make

Me sentire vim doloris, me feel the strength of grief,

Fac ut tecum lugeam. that I may grieve with you.

Fac ut ardeat cor meum Make my heart burn

In amando Christum deum, with love for Christ the Lord,

Ut sibi complaceam. that I may be pleasing to Him.

Virgo virginum preclara, O Virgin, foremost of virgins,

Jam michi non sis amara, be not bitter towards me:

Fac me tecum plangere. make me weep with you.

Fac ut portem Christi mortem Make me bear the death of Christ,

Passionis ejus sortem, the fate of His suffering,

Et plagas recolere, and recall His wounds.

Fac me plagis vulnerari, Let me be hurt by [theses] wounds,

Cruce hac inebriari be inebriated by this cross,

Ob amorem filij. because of love of your Son.

Inflammatus et accensus, Inflamed and incensed,

Per te virgo sim defensus may I be defended by you, O Virgin,

In die judicij. on the Day of Judgment.

Fac me cruce custodiri. Cause me to be guarded by the cross,

Morte Christi premuniri, to be made safe by the death of Christ,

Confoveri gratia. to be blessed by grace.

Quando corpus morietur, When my body dies,

Fac ut anime donetur cause the glory of paradise

Paradisi gloria. Amen. to be given to my soul. Amen.

—attr. Fra Jacopone da Todi

Tenor:

Comme femme desconfortée, Like a woman in agony,

Sur toutes autres esgarée, distraut above all others,

Quy n’ay jour de ma vie espoir, I am one who has no further hope in life

D’en estre en nul temps consolée, and cannot ever be consoled,

Mais en mon mal plus agravée but is ever more aggrieved by her misfortune

Desire la mort main et soir. and wishes for death night and day.

(Tenor text taken from Binchois’s

rondeau in Dijon 517, fol. 41’-42)

INTERMISSION

Audi benigne Conditor Orlande de Lassus

(see above)

Emendemus in melius William Byrd

Emendemus in melius que Let us amend for the better those sins we

ignoranter peccavimus ne in ignorance have committed, lest being

subito preoccupati die mortis overtaken suddenly on our day of death

queramus spatium penitentie we seek a time for penitence

et invenire non possumus. and cannot find it.

Attende, domine, et miserere, Harken, O Lord, and have mercy,

quia peccavimus tibi. for we have sinned against you.

Adiuva nos, deus salutaris noster, Help us, O God of our salvation,

et propter honorem nominis tui and, for the glory of your name,

libera nos. deliver us.

Christe qui lux es et dies William Byrd

Christe, qui lux es et dies, Christ, who art light and day,

noctis tenebras detegis, who uncovers the dark of night,

lucisque lumen crederis, whom we believe to be the light of light,

lumen beatum predicans. proclaiming blessed light.

Precamur, sancte domine, We beseech you, holy Lord,

defende nos in hac nocte, to defend us this night.

sit nobis in te requies, May our rest be in you,

quiemtam noctem tribue. as you grant us a quiet night.

Ne gravis somnus irruat, Let not heavy sleep seize us,

nec hostis nos surripiat, nor the enemy take us,

nec caro illi consentiens, nor the flesh, yielding to the enemy,

nos tibi reos statuat. make us sinful before you.

Oculi somnum capiant, Let our eyes grasp sleep,

cor ad te semper vigilet, but our heart remain vigilant to you;

dextera tua protegat may your right hand protect

famulos qui te diligunt. your servants who love you.

Defensor noster aspice, Our defender, look on us,

insidiantes reprime, restrain the insidious,

guberna tuos famulos, govern your servants

quos sanguine mercatus es. whom you have redeemed with your blood.

Memento nostri domine, Be mindful of us, O Lord,

in gravi isto corpore, in this burdensome body,

qui es defensor animae, who art the defender of the soul:

adesto nobis, domine. Amen. be with us, O Lord. Amen.

—(Hymn for Compline)

Lamentationes Ieremiae (Secunda pars) Thomas Tallis

Caph. Caph.

Omnis populus eius gemens et quaerens All her people groan as they search for

panem. Dederunt preciosa quaeque pro bread. They have given their precious things

cibo ad refocillandam animam. Vide, for food to revive their spirits. See, O Lord,

Domine, et considera quoniam facta sum and consider how worthless I have

vilis. become.

Lamed. Lamed.

O vos omnes qui transitis per viam, All ye who pass by on the way,

attendite et videte si est dolor sicut look and see if there is any sorrow like

dolor meus, quoniam videmiavit me my sorrow, which was brought upon me

ut locutus est Dominus in die irae as the Lord said in the day of his fierce

furoris sui. anger.

Mem. Mem.

De excelso misit ignem in ossibus meis, From on high he hath sent fire into my bones,

et erudivit me, expandit rete pedibus and he spread net and opened it for my

meis, convertit me retrorsum. Posuit feet; he turned me back. He has left me

me desolationem; tota die moerore desolate, faint

confectam. all day long.

Ierusalem, Ierusalem, convertere ad Jerusalem, Jerusalem, turn to the Lord

Dominum Deum tuum. your God.

O vos omnes Alfonso Ferrabosco

O vos omnes qui transitis per viam, All ye who pass by on the way,

attendite et videte si est dolor similis look and see if there is any sorrow like

sicut dolor meus. my sorrow.

Timor et tremor Orlande de Lassus

Timor et tremor venerunt super Fear and trembling have come over me,

me, et caligo cecidit super me: and darkness has fallen over me:

miserere mei, Domine, have mercy on me, O Lord,

quoniam in te confidit anima mea. for my soul has trusted in you.

Exaudi, Deus, deprecationem Hear my prayer, O God, for

meam, quia refugium meum es you are my refuge and my strong

tu et adutor fortis. Domine, helper. O Lord, I have implored

invocavi te, non confundar. you: let me not be confounded.

—Psalm 54: 6; 30: 18

POMERIUM, founded by Alexander Blachly in New York in 1972 to perform music composed for the famed chapel choirs of the Renaissance, derives its name from the title of a treatise by the 14th-century music theorist Marchettus of Padua. In the introduction, Marchettus explains that his Pomerium (literally, “garden”) contains the fruits and flowers of the art of music. Widely known for its interpretations of Du Fay, Ockeghem, Josquin, Palestrina, and Lassus, the modern Pomerium is currently recording a series of compact discs of the masterpieces of Renaissance a cappella choral music, of which the thirteenth, titled Orlande de Lassus: Motets & Magnificat, was released on Pomerium’s own Old Hall Recordings label in 2008. Pomerium’s thirteenth recording in this series is titled A Voice in the Wilderness: Mannerist Motets of the Renaissance.

Alexander Blachly is the 1992 recipient of the Noah Greenberg Award given by the American Musicological Society to stimulate historically aware performances and the study of historical performing practices. He has been active in early music as both performer and scholar since 1972. Mr. Blachly earned his post-graduate degrees in musicology from Columbia University and assumed the post of Director of Choral Music at the University of Notre Dame in 1993. In addition to Pomerium, Mr. Blachly directs the University of Notre Dame Chorale and Chamber Orchestra.

For bookings, please contact

Wendy Redlinger,

Senior Arist Representative

GEMS Live!

(802) 254-6189

wredlinger@gemsny.org

GEMS

Gotham Early Music Scene

340 Riverside Drive, Suite 1-A

New York, NY 10025

(2120 866-0466

http://www.pomerium.us

This concert is made possible, in part, with funding from

the New York State Council on the Arts.

From his 1589 collection of hymns for the whole year comes Palestrina’s Vexilla regis prodeunt, with magnificent words by Venantius Fortunatus (6th cent.) for Passion Sunday. In contrast to his more rhetorical setting of Super flumina Babylonis heard earlier, here Palestrina adopts his favored style of fluent, smoothly unfolding counterpoint, with verses in polyphony alternating with verses in chant in the same time-honored fashion as in Du Fay’s hymn at the beginning of our program. Like many polyphonic hymn composers from the beginning of the sixteenth century, Palestrina expands the final polyphonic stanza from four to five voices, with the added voice and top voice sounding in strict, slow-motion canon.

Vexilla regis Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina

Vexilla regis prodeunt, The banners of the king proceed:

Fulget crucis mysterium, now gleams the mystery of the cross,

Quo carne carnis conditor that gibbet which upon was hung,

Suspensus est patibulo. in flesh, the maker of all flesh.

Quo vulneratus insuper The cross on which he, wounded too

Mucrone diro lancee, by the dreaded lance’s point,

Ut nos lavaret crimine, blood and water forth did bleed

Manavit unda et sanguine. to cleanse us of our sin.

Impleta sunt que concinit Now see fulfilled the prophecy

David fidelis carmine, that faithful David sang,

Dicens in nationibus: saying to the nations, this:

Regnavit a ligno deus. Our God upon a tree has reigned.

Arbor decora et fulgida, O lovely, shining tree, adorned

Ornata regis purpura, with purple of the King,

lecta digno stipite chosen, with your worthy trunk,

Tam sancta membra tangere. such sacred limbs to touch.

Beata, cujus brachiis Blessed tree, whose branches held

Saecli pependit pretium, the treasure of the world:

Statera facta corporis, a balance from his body made

Praedamque tulit Tartari. to bear the prize of Tartarus.

Fundis aroma cortice, You pour upon the bark sweet spice,

Vincis sapore nectare, you conquer with sweet nectar’s scent,

Iucunda fuctu fertili and with a pleasant fertile fruit

Plaudis triumpho nobili. the noble triumph you applaud.

O crux, ave, spes unica, Hail, O cross, our only hope,

Hoc passionis tempore, at this the passiontide:

Auge piis justitiam, to the just give justice more,

Reisque dona veniam. and mercy sinners grant.

Salve, ara, salve, victima, Hail, O altar, victim, hail,

De passionis gloria glory of the passion’s duel,

Qua vita mortem pertulit, that by which life death removes

Et morte vitam reddidit. and too from death life is restored.

Te summa, deus, trinitas, To you, O God, high Trinity,

Collaudet omnis spiritus may every spirit sing forth praise,

Quos per crucis mysterium whom by the mystery of the cross

Salvas: rege per secula. Amen. you’d save: now ever be our King! Amen. —Venantius Fortunatus (6th cent.) —Trans. A.B.