Sept. 27, 2014 Yale University

PROGRAM

MUSIC FOR HOLY ROMAN EMPEROR MAXIMILIAN I AT THE 1518 DIET OF AUGSBURG

|

Argentum et aurum (chant antiphon) La Morra |

Regensburg 4306 (1501) Henricus Isaac |

(played on viols)

|

Virgo prudentissima (chant antiphon) |

Antiphonale Pataviense, 1511 |

Intermission

MUSIC FOR MARTIN LUTHER AT THE 1530 DIET OF AUGSBURG

| Non moriar sed vivam, 4v | Ludwig Senfl (ca. 1486-1542) |

MUSIC FOR HOLY ROMAN EMPEROR CHARLES V AT THE 1548 DIET OF AUGSBURG

|

Ave Maria, 6v Ich stuend an einem Morgen, 4v |

Ludwig Senfl Ludwig Senfl |

(played on viols)

|

Missa Sur tous regrets, 5v, Kyrie Carole, magnus erat, 5v |

Nicolas Gombert (ca. 1495-1560) Thomas Crecquillon (ca. 1490-1557) |

Pomerium

Kristina Boerger, Melissa Fogarty, Michele Kennedy, Dominique Surh – sopranos

Luthien Brackett, Silvie Jensen – mezzo-sopranos

Neil Farrell, Michael Steinberger, Christopher Preston Thompson – tenors

Jeffrey Johnson, Thomas McCargar – baritones

Kurt-Owen Richards, Peter Stewart – basses

The Cat’s Paw

Mary Anne Ballard, John Mark Rozendaal, James Waldo – viols

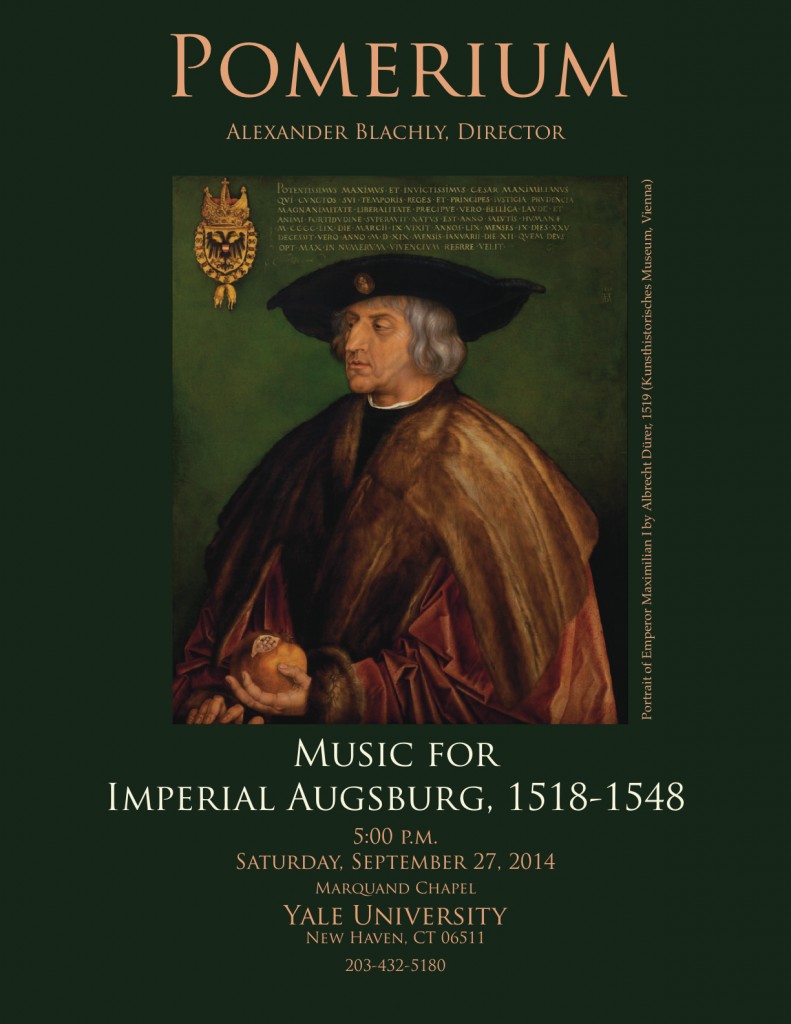

Commentary on the Programby Alexander Blachly The Holy Roman Empire officially came into existence with the coronation of Charlemagne by Pope Leo III on Christmas Day, 800 AD. Known at that time as the Empire in the West, it encompassed almost all of modern Europe except for Spain and Britain. It acquired the name of Holy Roman Empire (Imperium Romanum Sacrum or Heiliges Römisches Reich) in the thirteenth century. Though its boundaries changed over time, the Empire lasted from 800 until August 6, 1806, just over a thousand years; and until well into the sixteenth century the two most powerful rulers in Europe were the emperor and the pope. The emperor’s primary role was to defend Christendom against Islamic armies from the Middle East, which periodically conquered territories in eastern Europe and then threatened to advance into western Europe. The emperor in his military role was a medieval knight, duty-bound to wage war on Christendom’s enemies. By the late Middle Ages, the Empire no longer included France, being limited primarily to the German-speaking countries. It held its Diets (or Reichstage or General Assemblies) in such cities as Augsburg, Worms, Regensburg, Prague, and Speyer. Among the more renowned of the Diets were those at Augsburg in 1518, when Luther, a year after nailing his 95 theses to the door of the castle church in Wittemberg, defended himself before the papal legate, Cardinal Cajetan; at Augsburg in 1530, when Philipp Melanchthon presented a statement of Lutheran positions that became known as the Augsburg Confession; and again at Augsburg in 1548, when the Augsburg Interim recognized the legitimacy of Lutheranism and allowed Protestant clergy to marry. (In 1546, though, the Emperor had embarked on a campaign to eradicate Protestantism from Europe, and it wouldn’t be long before the fragile 1548 peace between Protestants and Catholics broke down, decades later erupting in the Thirty Years War of 1618-1648.) At the 1518, 1530, and 1548 Diets in Augsburg the emperor was present. In 1518 it was emperor Maximilian I, who died in January of the following year. Maximilian was so fond of the city that he had come to be known as “the Burgomaster of Augsburg.” In 1530 and 1548 the emperor was Maximilian’s grandson, emperor Charles V, then at the height of his power. The mission of the emperor expanded after 1517: now it was both to defend Christendom against the threat of Islam and to deal somehow with Protestantism. Emperors Maximilian and Charles V were notable patrons of the arts and great lovers of music. Both would have brought with them to the Diets their chapels, that is, their musical establishments, which were among the most renowned in Europe. The first half of today’s program presents music by Isaac and Senfl, the greatest composers of the Imperial Chapel during the reign of Maximilian I; the second half features works by Senfl, who composed several pieces specifically for the 1530 Diet, and by the principal composers for the Imperial Chapel during the reign of Charles V, i.e., Gombert and Crecquillon. These works are grand in scale, rich in texture. Maximilian’s was a German chapel that featured German singers and composers. Charles’s chapel, which he called his Capilla flamenca (“Flemish choir”), was comprised almost exclusively of singers and composers with Flemish names. Royal and aristocratic choirs at this time typically assigned three voices to each of the lower lines (which had such labels as bascontre, haultecontre, and haulteneur) and as many as seven to ten voices to the top line (normally unlabeled). With few exceptions, we don’t know precisely what music was sung at the various Diets nor at what events in the programs, though we can be sure that Masses were celebrated with the greatest ceremony and with the most impressive music. At state dinners and other assemblies of prince-electors, one can easily imagine motets being performed, especially large-scale works that praised the emperor and the empire. Isaac’s Missa Argentum et arum (“Silver and Gold Mass”) takes its name from an antiphon for the feast of Saints Peter and Paul (June 29). Isaac’s opening Kyrie is especially arresting. Here, against long-held notes in the Bassus, the three upper voices sing the antiphon melody and echoes of it at three different speeds, with each voice limited to a single note-value: dotted breves in the Discantus, dotted semibreves in the Altus, and dotted longs in the Tenor. The shortest of these values is in the Altus, which sings notes one-and-a-half times the length of the tactus (beat). When watching the conductor while listening to the music, one gets the impression of things being out of sync, especially in the Altus part, despite the regularity resulting from the repetition of unvaried note-values. At the Christe, the beat remains the same, but now notes tend to occur on the beat, such that one has the physical sensation of an increase in the speed of the music. This is only the beginning of a series of compositional experiments by the ever-inventive Isaac, who was clearly confident that his audience would be sophisticated enough to appreciate his ingenuity. Much could be said about the remainder of the Kyrie and the entirety of the Gloria, but let it suffice here to note that the most striking moments of the latter movement occur when two or three voices get caught in what feels like a loop of repeating two-chord cadences—dominant seventh to tonic, in later terminology—which doesn’t change during the course of the presentation of the entire antiphon melody in another voice, despite the ensuing dissonances. It is an effect that sounds surprisingly modern to our ears, and must have sounded that way to Isaac’s audience as well. Scholar David Rothenberg has shown how the images of the Most Prudent Virgin were used by Maximilian to draw implicit parallels with himself as emperor: “both she and he were sovereign monarchs, she of heaven, he of the Holy Roman Empire.” The Virgo prudentissima chant, which borrows imagery from the Song of Songs and Book of Revelation, is the antiphon for the Magnificat at the Feast of the Assumption, when Mary ascended into heaven to become queen, wearing a crown of stars. Isaac’s great six-voice motet Virgo prudentissima was originally composed for the Reichstag in Constance in 1507. The text, in learned hexameters by Maximilian’s chapel master, Georg Slatkonia, invokes the image of Mary surrounded by angels and holy armies at her coronation, “melting the stars beneath her shining feet with brilliant beams and gleaming light.” In the second pars, Slatkonia, after calling upon the archangels Michael, Gabriel, and Raphael to pray to Mary on behalf of the sacred Empire and emperor Maximilian, mentions himself as the emperor’s cantor and chapel master and also as the prelate of Pedena. In a later version of the work, the text has been updated to refer to Slatkonia as the prelate of the region of Austria, i.e., Bishop of Vienna, a position he assumed in 1513. It is on the basis of this change that we know that Isaac’s motet was presented a second time, perhaps at the great 1518 Diet of Augsburg, when Maximilian would have wanted to align all of his power and glory against the challenge posed by Martin Luther. Ludwig Senfl, who began his career as a choirboy in Maximilian’s Imperial Chapel in 1496 and continued to sing in it until Maximilian’s death in 1519, thereafter spent most of his career in Munich in the service of the duke Wilhelm while also providing music for duke Albrecht of Prussia. Senfl never relinquished his Catholic faith, though he did resign the priesthood in order to marry. Despite his adherence to Catholicism, he was attracted to Luther’s ideas and became a personal friend of the reformer. Shortly before the end of the 1530 Diet of Augsburg, Luther asked Senfl for a motet. The composer obliged with Non moriar sed vivam, a setting of Psalm 118, verse 17. Each of the four voices in turn sings the words of the verse in slow motion to the melody of Psalm Tone 7, one of the eight traditional formulas that had been used for chanting Psalms for hundreds of years. The other voices anticipate the formula before each entry and then accompany it with suave counterpoint. Luther, who was no slouch of a musician, was impressed: “I could never compose a motet like Senfl’s, even were I to tear myself to pieces in the attempt,” he declared. Maximilian had been dead for eleven years by the time of the 1530 Augsburg Diet, succeeded by his grandson Charles V. Perhaps Charles heard Non moriar sed vivam on that occasion. At the 1548 Diet he may also have heard Senfl’s six-voice Ave Maria, first printed in 1537. In a display of extraordinary virtuosity, this enormous motet, based on Josquin’s classic four-voice original, has the Tenor primes intone the opening melodic phrase of Josquin’s setting a total of fourteen times (twice the Marian number of 7), usually in slow motion, but eventually at faster speeds as well. One might expect fourteen entries of the same phrase to become tedious, but in listening we enjoy each of the statements in turn because of the ever-changing contrapuntal contexts (constantly echoing Josquin’s motives) Senfl creates for them. In the 1542 print of Gombert’s Missa Sur tous regrets by the firm of Scotto, there is inscribed the rubric “A la Incoronation,” which suggests that it was sung at Charles’s second coronation, on February 24, 1530, in Bologna. Perhaps it was sung again in April of that year at the 1530 Diet, and perhaps again eighteen years later at the 1548 Diet. Charles on these occasions could well have wished to show off music so rich-textured, densely contrapuntal, and glowing with harmonies that sparkle like embers in a fire—truly polyphony for sophisticated tastes. Though Gombert never enjoyed the title of “maître de chapelle,” he was evidently Charles’s favorite court composer, later succeeded by Thomas Crecquillon, who enjoyed the title of “maître de chapelle” for a period of seven years. Crecquillon’s music forgoes the rich passion of Gombert’s in favor a cooler, more elegant classicism. Though no occasion for the motet Carole, magnus erat is now known, its celebration of Charles V has the hallmarks of a celebratory work to be performed at an imperial Diet, since it compares Charles V favorably to Charlemagne, the founder of the empire. Significantly, Charles is glorified not only as a warrior who surpasses “Charles the Great” in arms, but even more as “Charles the Greatest” because of his belief that a “far greater glory is to be devout.” A note on the pronunciation of Latin in today’s concert: For the music by Isaac and Senfl composed for Maximilian’s German singers, and for Senfl’s Non moriar and Ave Maria, which were evidently composed for German-speaking choirs as well, we adopt a “Germanic” pronunciation of Latin. For the music by Gombert and Crecquillon composed for Charles V’s Flemish singers, we adopt a “Franco-Flemish” pronunciation. |