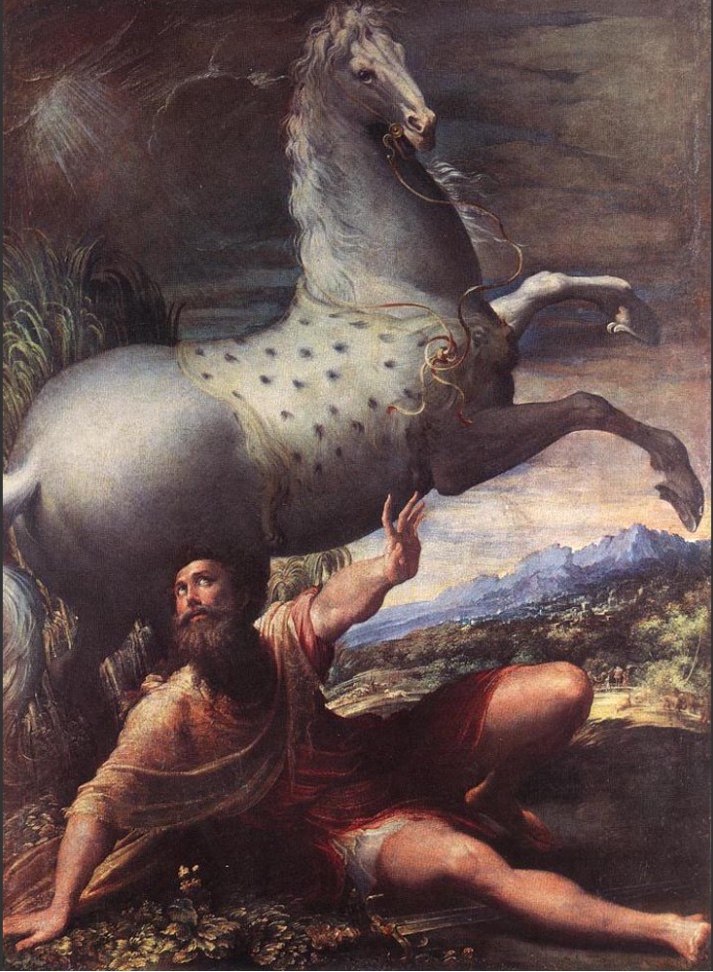

Clear parallels exist between Mannerist painting and Mannerist music. The Mannerist composer Giaches de Wert chose texts that recount miraculous events or ones of extreme emotion as his preferred words to set to music. Inspired, perhaps, by Parmigianino’s depictions of the Conversion of St. Paul, in Saule, Saule (published in 1581) Wert has Saul hear a distant voice from heaven coming closer and louder. In a frightened voice Saul asks, “Who are you?” As an evocation of the full force of Jesus’ voice thundering down “I am Jesus, whom you are persecuting!” a wave of sound from eight separate voice-parts calls out the words in close repetition. Then comes Jesus’ powerful command: “Arise and go to the city!” To express sorrow (Vox in Rama), Wert drew on the technique, established earlier in the sixteenth century for this purpose, of descending chromatic scales. To express extreme emotion, he favored large melodic leaps and unstable harmonies (Vox in Rama and Vox clamantis in deserto). To express the churning waves of the Sea of Galilee when Jesus and his disciples are caught in a violent windstorm (Ascendente Jesu), he has all six voices collide in rapid, out-of-phase syncopations.

Where Wert specialized in theatrical effects, Gesualdo explored the psychological realms of despair, sorrow, and guilt. Daring chromatic effects and searing dissonances are his trademark, especially prominent in the twenty-seven large-scale responsories he wrote for Holy Week. Tonight we hear one of the shortest but most powerful of these, O vos omnes. In a truly Mannerist move, Gesualdo begins his setting on the most unstable of bass notes: B-natural, a ninth below middle C. (Wert’s Vox in Rama begins on the same bass note.) The excruciating chromaticism of “si est dolor similis sicut dolor meus” (“if there is any sorrow like my sorrow”) combines both pain and sweetness, emotions the murderous but guilt-ridden Gesualdo well understood and which he had a particular aptitude for expressing in the largely imitative polyphonic idiom of the Renaissance. In that style, high, low, and middle voices echo each other throughout the texture, in effects that at times are juxtaposed to chordal passages, as at “o vos omnes, qui transitis per viam, attendite et videte.” No matter how far they depart from stability, Gesualdo’s chromatically tangled lines of polyphony always cadence in pure major triads.

Slovene composer Jacobus Gallus, who lived and worked in Moravia and Bohemia at the end of his life, created in his Christmas motet Mirabile mysterium one of the most unusual works of the Renaissance. The words proclaim that “on this day a miraculous mystery is declared, with [divine and human] natures having been altered. God is made man, and that which he was [i.e., divine] he remains; that which he was not [i.e., human] he assumes, suffering neither commixture nor division.” Each phrase in this text provides a rationale for Gallus to introduce ever more unstable and conflicting chromatic effects, with the overthrow of the normal rules of musical composition representing the overthrow of the normal rules of nature.

The great scholar of Renaissance music, Edward Lowinsky, was so impressed by the chromatic effects of Andreas de Silva’s Omnis pulchritudo Domini, expressive of the miracle of Ascension, that he thought the composer must have been Spanish. It appears now that Silva was probably Flemish, but writing in an idiom ahead of his time. (Omnis pulchritudo Domini is preserved in the Medici Codex of 1519.) The slow-moving cantus firmus enters late and in the middle of the texture. Once having entered, its long notes, which guide and control the four other voices, allow Silva to generate unexpected, strange harmonies—harmonies evocative of the miracle of Ascension that is being declaimed in two texts simultaneously. The musical evocation of the meaning of the words being sung, heard here in a striking way, would soon become the nearly universal goal of composers of Mannerist music.

A word, finally, on the single work by Monteverdi heard here. Originally a madrigal written to an Italian text, Tu vis à me abire shows Monteverdi’s skill in representing the emotions of the abandoned lover of Guarini’s Rime, madrigal 83. Six years after Monteverdi’s setting appeared in print in his Book IV of 1603, Aquilino Coppini, a skilled rhetorician from Milan, replaced Guarini’s Italian “You are abandoning me, hard soul! What harshness to be the soul of someone’s heart and to separate oneself while feeling no sorrow!” with sacred Latin words spoken by Jesus: “You wish to leave me, hard soul! What extreme duress to cleave to fallen ones and to be separated from eternal glory!” Most notable in both versions is how Monteverdi depicts “separation,” with voices that begin a phrase in unison slowly pulling apart. Monteverdi’s music has a dramatic and operatic feel, presaging effects in the actual operas that soon would win the composer his greatest acclaim, beginning with L’Orfeo of 1607.