October 22, 2017

This concert is part of the New York Early Music Celebration [2017]: Holland & Flanders. www.NYEMC.org

Flemish Musical Mastery in the Age of Hieronymus Bosch

|

O crux splendidior (6-voice motet) |

Orlande de Lassus (1532-1594) |

INTERMISSION

|

Salve crux, arbor vite (5-voice motet) |

Jacob Obrecht |

Pomerium

Kristina Boerger, Martha Cluver, Sarah Hawkey, Chloe Holgate, Dominique Surh – sopranos

Patrick Fennig, Peter Gruett – countertenors

Nathaniel Adams, Neil Farrell, Emerson Sieverts, Michael Steinberger, Christopher Preston Thompson – tenors

Thomas McCargar – baritone

Kurt-Owen Richards, Peter Stewart – basses

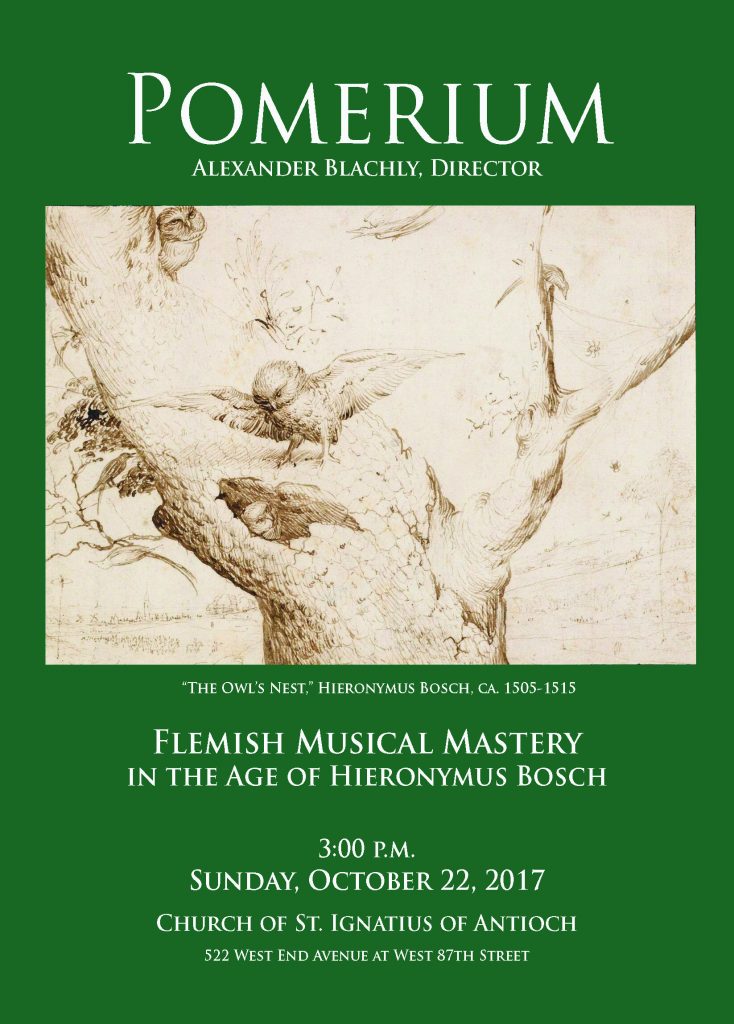

In response to a request from the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, Pomerium has prepared a program of music to complement to the Gallery’s exhibition “Bosch to Bloemaert: Early Netherlandish Drawings from the Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam,” which will be on view from October 8, 2017, to January 7, 2018. (Pomerium will present its concert at the National Gallery of Art on Oct. 29, 2017, one week after the premiere of the new program in New York on Oct. 22.) The images in the exhibition initially impress us by their extraordinary precision of detail. Even when the subject is as charming or as whimsical as Hieronymus Bosch’s Owl’s Nest, a pen and ink drawing from ca. 1505-1515, our first reaction may be to marvel more at the minute features of feathers on the wing of the central adult owl or the bumpy bark of the tree trunk than at the drawing’s larger subject matter. These details in the foreground, so precise in their rendering, initially eclipse everything else, so that we may only realize later that there is a background, sketchily drawn. The ability to transfer immediate details of our visual experience of the physical world to paper or canvas with such seeming lifelike accuracy was not a talent unique to Bosch or to only a few exceptional individuals from northern Europe in the Renaissance. On the contrary, it was a skill possessed by every artist whose works form the current exhibition, and by many other Northern artists besides.

Precision of detail was also the most characteristic feature of the music by Netherlandish composers of the time. Their music did not take the world of nature as a starting point (there are no bird calls or barking dogs in Netherlandish music), but all of the composers in today’s program shared a mastery of minute details of counterpoint and voice-leading that impress the listener with their skillful moment-by-moment obedience to musical “laws of nature.” We will not hear in today’s pieces such features of medieval music as clashing dissonances or outré melodic leaps. Nor will we find the music arranged in the abstract rhythmic patterns that characterize polyphony from the thirteenth century. The default melody is flexible and shapely, with phrases making an effect comparable to the roundness of a branch or the softness of human limbs defined by light and shadow. Such phrases invite shapely performance.

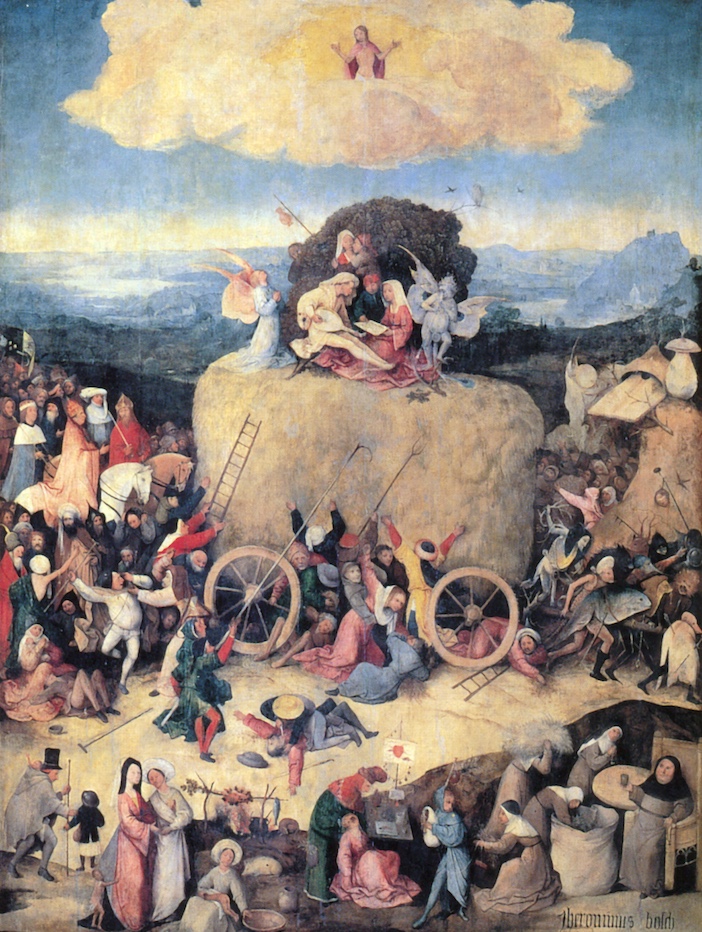

Significantly, the Netherlandish visual artists were not content simply to mirror nature. Often their drawings and paintings convey a moral message. In the Owl’s Nest, the message seems straightforward: the adult owl in the center of the drawing is teaching a young bird how to fly, and we almost unconsciously make the connection that for the old to teach the young is “natural,” something that adult humans likewise do “naturally” for their children. In the famous Haycart triptych of ca. 1485, Bosch conveys a more complicated message. In the first place, this brightly-colored painting seems only tangentially related to the real world. It bears, rather, the aspect of a dream or, in the right-hand panel, a nightmare. This is Bosch’s allegory on the destructive nature of greed. The hay piled dangerously high on the cart represents wealth, which people from various walks of life try to pry loose with pitch forks, or try to clamber aboard with a ladder, or claw at with their hands. Rat-like monsters draw the cart toward hell, depicted in the right-hand panel, and away from Earthly Paradise, depicted in the left-hand panel. The Pope and Emperor follow directly behind the haycart. They too have fallen prey to the hay’s lure. Other people are about to be run over by the cart’s wheels or are being crushed by those deperately rushing to grab what they can. Only the musicians atop the haystack and the monk drinking wine in the lower right corner seem at peace. Perhaps that is because the musicians are captivated by sweet sounds, while the monk feels no need for worry so long as the nuns to the left of his table are filling a sack with handfuls of hay.

One might imagine that vocal music, with its sung text, could convey a narrative message as complex as Bosch’s Haycart; but only in the last phase of the period in which Netherlandish musicians dominated Europe’s musical courts—when Orlande de Lassus and Giaches de Wert were in their prime in the 1560s, ’70s, and ‘80s—had musical style evolved to the point where melodies and harmonies could be directly illustrative of ideas, whether narrative or psychological. The vivid evocation of emotional states by composers active in the later sixteenth century stands in marked contrast with all earlier polyphony (some pieces by Josquin excepted). Most early Netherlandish vocal music not only lacked the stylistic means to yoke musical expression to textual expression (a possibility in which composers of the time rarely exhibited any interest), but their sacred polyphony focused almost exclusively on the setting of ritual texts, such as the Ordinary of the Mass: Kyrie, Gloria, Credo, Sanctus, and Agnus Dei. Ritual words, whether of the Mass or Office, were heard innumerable times throughout the year and expressed only generalized sentiments, e.g., Christian dogma in the Credo, or prayers for mercy on joyful as well as sad occasions.

But the Netherlandish composers had another way of anchoring even a liturgical text to a specific idea: by the use of a pre-existent melody (with its associated words) as the foundation for any sort of vocal polyphony whatsoever, whether Mass Ordinary, Marian antiphon, sacred motet with newly written words, or secular song. The sounding of the two texts at the same time created a commentary on the one by the other, prompting nearly the same level of “interpretation” by the listener as that required by the viewer of moralizing Netherlandish visual works of art. In today’s program, four pieces employ pre-existent foundation melodies with their own words in this way: the Gloria from Du Fay’s Missa Ecce ancilla Domini (the foundation melody being two Marian antiphons: “Ecce ancilla Domini” for the Annunciation and “Beata es, Maria” for the Visitation), Obrecht’s grand motet Salve crux, arbor vite (the foundation melody being the hymn “O crux lignum triumphale,” used by his teacher, Antoine Busnoys, as the foundation melody for an entire Mass), Josquin’s Stabat mater (the foundation melody being the rondeau tenor of Binchois’s “Comme femme desconfortée”), and the Agnus Dei from Compère’s Missa L’homme armé (the foundation melody being the song “L’homme armé”).

Even in works on today’s program that do not employ multiple sets of words sounding simultaneously—works which therefore require no bi-textual “interpretation” by the listener—we still hear the primary defining feature of Netherlandish music from the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries: the skillful manipulation of melodies interacting in a web of counterpoint to create richly inventive polyphony. Two of today’s pieces were originally composed as abstract instrumental studies without words, to which sacred words were added early in the sixteenth century: Isaac’s Reple tuorum corda (transmitted in most sources as the instrumental carmen La Morra) and Agricola’s Ave que sublimaris (a polyphonic study, wordless in most sources, based on the tenor of Binchois’s “Comme femme desconfortée”—the same melody that Josquin uses as foundation melody in his Stabat mater). In music by Du Fay and Ockeghem, the technique of pervading imitation, whereby all voices of a piece engage in singing the same melodic motifs at different times, often starting on a different pitch of the scale, was just emerging. It would soon vie with the related technique of canon, whereby more than one voice reads the same notated music, but each interprets it differently, following some verbal or other clue. Josquin was the first master of both canon and pervading imitation, the hallmarks of his works in all genres. Some notable earlier examples had appeared sporadically in the prior generation, but his consistent approach served as the model for serious composition throughout the remainder of the sixteenth century. Martin Luther marveled at Josquin’s ability to execute contrapuntal feats, and his assessment still rings true: “Josquin can make the notes do as he wishes, while other composers must do as the notes demand.”

The two works by Josquin in today’s program illustrate his unusual ability to create moving emotional effects with music composed to a slow-moving foundation melody. His Stabat mater, as just mentioned, has the tenor of Binchois’s chanson “Comme femme desconfortée” sounding throughout. The chanson words express a lover’s extreme pain at losing her lover: “I am like a woman in agony, who has no further hope in life and cannot ever be consoled, but wishes for death night and day.” Josquin’s setting thereby casts Mary as the forlorn lover, whose loss of her beloved son Jesus causes her unbearable pain. In Inviolata, integra et casta es, Maria, the foundation melody comes from the chant sequence “Inviolata, integra et casta es, Maria.” Josquin has it sounding in canon at the upper fifth, with the temporal distance between “dux” (leading voice) and “comes” (companion voice) shrinking in each successive large section of the work, from three breves (whole notes) in Part I, to two breves in Part II, to one breve in Part III. The listener, however, hardly notices this rigidly architectonic ground plan, finding his or her attention drawn instead to the beguiling melodic fragments chasing each other throughout the piece in the foreground. Thus, the canon remains largely inaudible though controlling the work’s harmonies, while the elaborate pervading imitation that attracts our attention in the foreground has so graceful and elegant a profile that it seems to unfold independently of the ground plan.

The prize for Netherlandish contrapuntal acrobatics in today’s pieces goes to Loyset Compère, whose entire Missa L’homme armé has the famous “L’homme armé” tune (the foundation melody of over 40 polyphonic Masses during the Renaissance) sounding in the “wrong” mode on E (the Phrygian) rather than on F (modified Lydian with B-flat to sound like modern F major) or G (Mixolydian, modified by many composers by the addition of B-flat to sound like modern G minor). In Agnus I the tune appears in canon at the half-step, with Final on E and Final on F. The verbal instruction for how the “comes” is to read the notes differently from the “dux” typically requires some thought to decipher, challenging the performers to transform the apparent meaning of the notation as it appears on the page. The instruction in Agnus I is “Canon in e la mi,” with the tune notated on F for the “dux.” The “comes” is therefore to read the tune a half-step lower, as if notated on E. In Agnus III the instruction is “Fuga unius temporis in epithono,” with the tune notated on D. Again the “comes” is to read the tune as if the Final is on E, but now a whole step higher than notated. Once the puzzle of the instructions has been solved, the musical effect of consonant canons at such close pitch proximity seems almost miraculous.

Netherlandish contrapuntal virtuosity stands as the musical counterpart to the Netherlandish visual artists’ virtuosity in the realm of drawing and painting. Especially in the period under investigation, the more closely we examine Northern art, whether visual or sonic, the more admirable and thought-provoking it appears.